First part of a travelogue from Nagorno-Karabakh by Frantisek Staud

Text and photographs © by the author.

For the second part, click here.

Nagorno-Karabakh, at the first glance, does not make sense; it is inhabited mainly by Armenians but is internationally recognized as a part of Azerbaijan. Entry is possible through two roads – both leading from Armenia. Visas are granted by the Embassy of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh based in Yerevan, but once in your passport, you have closed the door to Azerbaijan. Neither the name of the enclave is utterly straightforward – a composite of the Russo-Persian “Nagorno Kara Bakh”, which translates as “mountainous black garden.” Unceasing border skirmishes and quarrels about political control of this elusive area scare many travelers. Yet, the country has so much to offer: mountain monasteries, archaeological sites, natural scenery and kindhearted people living lives that our (grand)grandparents told us about.

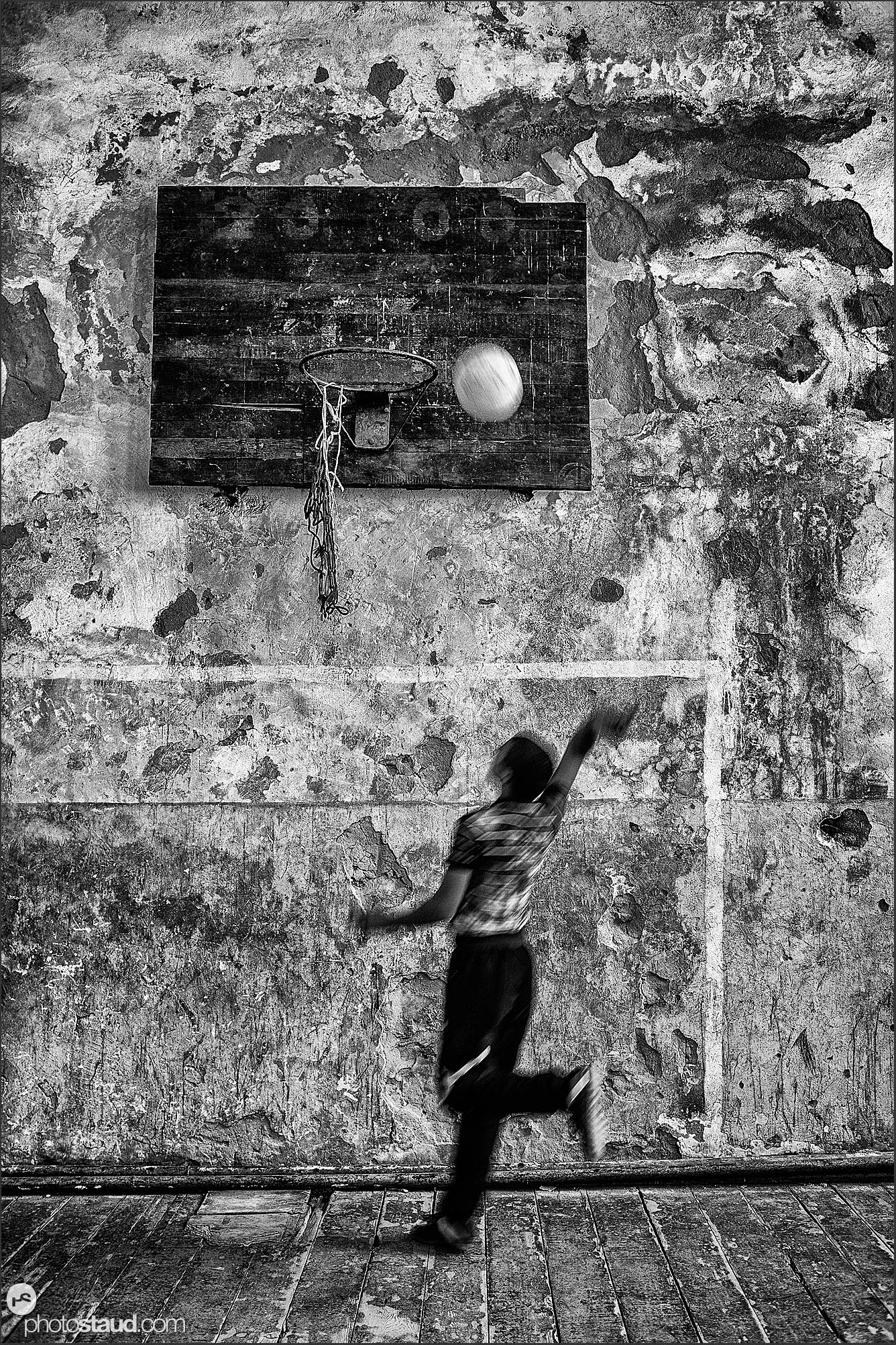

On the way to Karabakh I make a brief stop in an old Armenian village school of Halidzor. My visit and photography was pre-arranged by Volodya, with whom I drank vodka last night in a pub in nearby Goris. He promised the school would be pretty shabby, means photogenic, but he failed to mention that I would sink through the wooden classroom floor during history lesson. The decking of the gym is so disintegrated and patched that I’m afraid to move. Not the children who fearlessly, and in all the wildness, play basketball, football and handball – all at the same time. Igor, a teacher with a cigarette in his hand guides me around the school and when the classes are finished he invites me to his home. Sitting on the doorstep is his father, decorated with medals from the World War II (which assures him a relatively high pension of about one hundred US$ a month). But the greatest treasure is hidden behind the building – a vodka distillery! Incredibly amateur distillation apparatus starts with natural fireplace beneath a hanging cauldron, rusty pipes extending through the water tank (for cooling) and at the end, wonder of wonders, dripping in regular rhythm is this year’s crop. In Armenia, I soon realize that driving a car is not an acceptable excuse for not drinking; so before heading out to the serpentines of Nagorno-Karabakh I taste Igor´s delicious brandy.

In the late afternoon I climb into the mountains of the Black garden, pausing here and there to admire the beautiful landscape under the setting sun. After dusk, I arrive to the first Karabakh town of a few thousand inhabitants, Shusha. Twenty years ago, the war destroyed eighty percent of the buildings – and the town has still not recovered. The dark streets lead me towards a newly renovated Christian cathedral with an unpronounceable name, Ghazanchetsots, the only illuminated building around. In a nearby restaurant I order shashlik and ask about lodging. The best place to stay, I am told, must be at Saro Saryan´s; they all know him and he knows them all. He also knows the foreign minister Karen Mirzoyan, who will grant me a permission to visit the ghost town, Agdam.

In Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, I roam the gray streets and decline countless invitations to stakan of vodka. On the outskirts of the town I happen upon a children’s home. Its director, Nonna Musajeljan, is happy to walk me through the corridors with beautifully painted walls and introduces me to her smiling foster-children. After reaching the age of 18, they must leave this temporary home, but they all are given an apartment and a job by the government.

The old Hospital in Stepanakert is an aged Stalinist building constructed in 1936. It is Sunday morning and I do not expect anyone to let me in. Yet, I am lucky to meet the “glavnyj vratch” – the chief physician. Doctor Atayan, a gray-haired gentleman in his late 60´s, is kind enough to guide me through all departments of the hospital. Cracked walls, fissured plaster and crumbling floor tiles resemble anything but a hospital. The gloomy atmosphere of the dark corridors is, however, not reflected in the minds of the staff or patients – they are all extremely helpful and cooperative. The patients do not understand the purpose of my visit, but when I explain my journalist’s mission, they thank me for my interest – “spasibo za vnimanje.”

“We have nothing to complain! We have excellent doctors here,” they say in unison, “and pretty nurses,” they add. I have to agree.

Doctor Atayan explains to me how the hospital functioned during the war. “First we worked here, left or right wing of the building, depending on where the shooting was coming from. Then we had to move to the basement and eventually we left the building and relocated to the president´s house.” Numerous bullet holes in the hospital facade confirm the testimony. Through a broken window I see a brand new hospital being finalized, sponsored by patrons from Russia and the West. A metaphorical view that gives the doctors and patients a hope for brighter future.

Note: Nagorno-Karabakh is a mountainous enclave on the south side of the Caucasian massif surrounded by Azerbaijan but controlled by Armenia. As the object of power rivalry it was attached to Azerbaijan in 1921. In February 1988 riots for connecting the enclave to Armenia broke out in Stepanakert, the administrative center. The People’s Assembly had grown into an armed conflict and the war between Christian Armenia and Muslim Azerbaijan could begin. In six years, it claimed about 30,000 lives, hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis and Armenians were driven from their homes. Cease fire was declared in 1994, but a peace treaty has not been signed yet. At the time of preparing this report (Spring 2016) media inform on destabilization of the border – each side blaming the other for starting the violence.

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35954969

Photo gallery of Nagorno-Karabakh:

1 thought on “In the mountains of the Black Garden (I)”